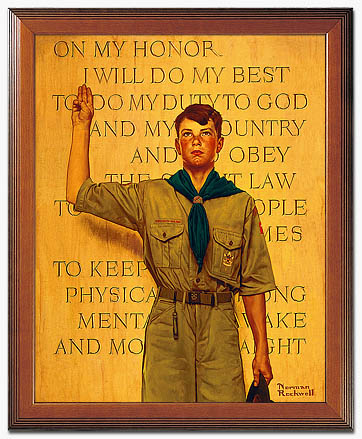

The Right of Free Association

Many people these days have the mistaken idea that private individuals must associate with people and organizations they find insulting and whose values they find antithetical to their own. While this may be true to a certain extent in the public context, it is not true concerning private voluntary associations. This basic freedom was upheld and firmly restated by the United States Supreme Court in Dale v. Boy Scouts of America:

Many people these days have the mistaken idea that private individuals must associate with people and organizations they find insulting and whose values they find antithetical to their own. While this may be true to a certain extent in the public context, it is not true concerning private voluntary associations. This basic freedom was upheld and firmly restated by the United States Supreme Court in Dale v. Boy Scouts of America:In Roberts v. United States Jaycees, 468 U.S. 609, 622 (1984), we observed that “implicit in the right to engage in activities protected by the First Amendment” is “a corresponding right to associate with others in pursuit of a wide variety of political, social, economic, educational, religious, and cultural ends.” ... Government actions that may unconstitutionally burden this freedom may take many forms, one of which is “intrusion into the internal structure or affairs of an association” like a “regulation that forces the group to accept members it does not desire.” Id., at 623. Forcing a group to accept certain members may impair the ability of the group to express those views, and only those views, that it intends to express. Thus, “[fSo, the bottom line here is that people who find homosexual behavior inconsistent with their personal faith and values are not required to continue private, voluntary associations they find offensive and people who do, do so at the risk of diluting or even defeating their own message to the contrary.]reedom of association … plainly presupposes a freedom not to associate.” Ibid.

Given that the Boy Scouts engages in expressive activity, we must determine whether the forced inclusion of Dale as an assistant scoutmaster would significantly affect the Boy Scouts' ability to advocate public or private viewpoints. This inquiry necessarily requires us first to explore, to a limited extent, the nature of the Boy Scouts' view of homosexuality.

The Boy Scouts asserts that it "teach[es] that homosexual conduct is not morally straight," Brief for Petitioners 39, and that it does "not want to promote homosexual conduct as a legitimate form of behavior," Reply Brief for Petitioners 5. We accept the Boy Scouts' assertion. We need not inquire further to determine the nature of the Boy Scouts' expression with respect to homosexuality. ...

We must then determine whether Dale's presence as an assistant scoutmaster would significantly burden the Boy Scouts' desire to not "promote homosexual conduct as a legitimate form of behavior." Reply Brief for Petitioners 5. As we give deference to an association's assertions regarding the nature of its expression, we must also give deference to an association's view of what would impair its expression. See, e.g., La Follette, supra, at 123-124 (considering whether a Wisconsin law burdened the National Party's associational rights and stating that "a State, or a court, may not constitutionally substitute its own judgment for that of the Party"). That is not to say that an expressive association can erect a shield against antidiscrimination laws simply by asserting that mere acceptance of a member from a particular group would impair its message. But here Dale, by his own admission, is one of a group of gay Scouts who have "become leaders in their community and are open and honest about their sexual orientation." App. 11. Dale was the copresident of a gay and lesbian organization at college and remains a gay rights activist. Dale's presence in the Boy Scouts would, at the very least, force the organization to send a message, both to the youth members and the world, that the Boy Scouts accepts homosexual conduct as a legitimate form of behavior.

Hurley is illustrative on this point. There we considered whether the application of Massachusetts' public accommodations law to require the organizers of a private St. Patrick's Day parade to include among the marchers an Irish-American gay, lesbian, and bisexual group, GLIB, violated the parade organizers' First Amendment rights. We noted that the parade organizers did not wish to exclude the GLIB members because of their sexual orientations, but because they wanted to march behind a GLIB banner. We observed:

"[A] contingent marching behind the organization's banner would at least bear witness to the fact that some Irish are gay, lesbian, or bisexual, and the presence of the organized marchers would suggest their view that people of their sexual orientations have as much claim to unqualified social acceptance as heterosexuals ... . The parade's organizers may not believe these facts about Irish sexuality to be so, or they may object to unqualified social acceptance of gays and lesbians or have some other reason for wishing to keep GLIB's message out of the parade. But whatever the reason, it boils down to the choice of a speaker not to propound a particular point of view, and that choice is presumed to lie beyond the government's power to control." 515 U. S., at 574-575.

Here, we have found that the Boy Scouts believes that homosexual conduct is inconsistent with the values it seeks to instill in its youth members; it will not "promote homosexual conduct as a legitimate form of behavior." Reply Brief for Petitioners 5. As the presence of GLIB in Boston's St. Patrick's Day parade would have interfered with the parade organizers' choice not to propound a particular point of view, the presence of Dale as an assistant scoutmaster would just as surely interfere with the Boy Scout's choice not to propound a point of view contrary to its beliefs.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home